Homilies for the 2020 Lenten Season by Sr. Constance Joanna, SSJD

Most of us have traveled through Lent this year becoming increasingly burdened by the darkness of the world around us – politically, economically, and personally – as the COVID-19 virus has exploded. During some of that time I have been preaching on Sundays either at St. John’s Convent or at St. George on Yonge. Because of the often chaotic nature of my days during this crisis, I have sometimes I have had to rely on revising previous homilies. And so I found myself looking for my favourite homilies – some I preached this year, a couple from other years.

In this last week of Lent I’d like to share with you my favourite homilies from Year A in our 3-year lectionary cycle, from Ash Wednesday through the fifth Sunday of Lent, and including the Feast of the Annunciation on March 25. It provides an interesting bridge between Lent 4 and Lent 5.

I hope these reflections may help you in your own walk through the darkness of our present world into the amazing, loving, joyful light of Christ as you prepare for Holy Week and Easter.

Ash Wednesday: RECALIBRATING

Readings: Joel 2:1-2,29-35; Ps 103:8-18; Matthew 6: 1-6, 16-21

There was an interesting (and to me really funny) story in the news last Thursday about a 21-year old man who drove his SUV into the streetcar tunnel down at Queen’s Quay. It took eight people to get him out with a special crane that ran on tracks, and the incident diverted streetcar traffic for several hours during the morning rush hour. Lots of money lost and spent for the city and the TTC. And his penalty? A fine of merely $425!

But why did he do such a thing the police asked? “I was just following my GPS” he said!

I think Ash Wednesday – and Lent as a whole – is about exactly that – following our GPS, or recalibrating when we have gotten off track. But the GPS we should be following is what one of my Sisters calls the God Positioning System – not that annoying disembodied voice that hounds you to turn left even if you want to turn right, even if turning left is going to lead you into a traffic jam, or Lake Ontario – or a streetcar tunnel. And when you don’t follow the voice’s instructions it just gets more and more stressed – until finally it gives up in despair and says “recalibrating, recalibrating, recalibrating.”

Our God Positioning System doesn’t do that. Its voice is not pushy or insistent. Rather it offers a gentle invitation to recalibrate our lives, to look at what is really important to us and set our course anew. Ash Wednesday, with the ritual of the imposition of ashes, is a reminder of our mortality. We have come from the dust of the earth and our bodies will return there. But that is not the end of the story because we are created by the original GPS – the voice of the creating God who said “let us make humankind in our image.” God’s image is stamped on us. And because we are made in God’s image we too have the gift of creativity and freedom – the freedom to choose which GPS we want to follow.

The scripture readings for today help us to do that. At first, though, it may seem as if we’re listening to two conflicting GPS voices. “Blow the trumpet,” says the prophet Joel, “sound an alarm – a day of darkness and deep gloom is coming. Call on the name of the Lord – anyone who does will be saved.”

But then in Matthew’s gospel, Jesus says “do not blow the trumpet” – don’t blow your own horn to advertise your piety. Practice your prayer and your care for the poor privately. Go into you room and shut the door and the God who created you, who sees you everywhere, will reward you. And Jesus makes it clear in other places that the reward we will receive is not an earthly reward but the reward of an intimate relationship with the God who created us and loves us

So which voice do we listen to? Blow the trumpet or don’t blow the trumpet? Well, both of course. Both are proclaiming the same essential message – pay attention to what is happening in the world around you, and position yourself so you are grounded, rooted, in the love of a God who said at Jesus’ baptism, and again on the mount of Transfiguration, “this is my Son, the Beloved – listen to him.”

Call the community to prayer, Joel says, that we may repent of our preoccupation with things, with what the Hebrew prophets constantly call “false gods.” Call on God’s name, not on the name of wealth or power or greed or ambition.

Go to prayer yourself, Jesus tells us – enter into that place of intimacy with God your creator where you too can hear God say “you are my beloved son, my beloved daughter.”

Both these voices of Ash Wednesday call us to a holy Lent, a Lent that is not about false piety or spiritual practices that we undertake just because we think we ought to, but a Lent where the trumpet calls the community to prayer, and where the inner voice calls the individual to prayer, and where individual and community come together to respond to Jesus’ invitation to accept his gift of himself – to receive the bread and wine of the Eucharist, the nourishment we need if we are to stay on course, to know we are God’s beloved sons and daughters..

And that is what it means to keep a holy Lent. Let me close with a story from the second century Christian literature, from a book called The Shepherd of Hermas.

“I was sitting on a hillside, rather pleased with myself. I was fasting, as I often did, denying myself food, and getting up very early to climb the mountain and pray. I felt in this way I could repay the Lord for some of the difficult things he went through for me. But then the shepherd approached me.

“What are you doing up here so early in the morning?” he asked.

“I’m observing a fast,” I said, “to the Lord.”

“What sort of a fast is that?”

“Oh, my usual. I abstain from food. Deny myself luxuries. Get up early. And pray.”

The shepherd didn’t look impressed.

“That’s not the sort of fast that pleases the Lord,” he said. “That’s not what God asks of you.”

He could see the puzzled look on my face.

“Look, God does not want you to deny yourself good things. That is no road to holiness. A true fast is to deny yourself bad things: keep God’s commandments, do what God says, reject evil thoughts and desires the moment they enter your imagination. Reject what is wrong and serve God with a simple, uncomplicated heart. If you do that, you are fasting – fasting in a way that pleases the Lord.”

Listen to the voice of your GPS: you are my son, my daughter, my beloved.

Lent 1: STANDING FOR THE GOOD

Readings: Genesis 2.15-17; 3.1-7; Psalm 32; Romans 5.12-19;Matthew 4.1-11

Sometimes at the beginning of Lent I feel a little gloomy about myself and my seeming inability to “make myself better.” Lent after Lent I give things up, take things on, and in general try to be a better person. I suppose most of us do that. But the reality is that Lent was never meant to be gloomy – it started in the early church as a time of preparation for baptism at Easter. Yes, we are reminded that we are all sinners. As St. Paul says in his letter to the Christians in Rome, “all have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God and all are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus (Romans 5.23-24).” Recognizing our sinfulness is actually good news because it reminds us that we will never be able to “make” ourselves perfect, no matter how many Lenten resolutions we make or Bible studies we attend. Only God’s grace working in us can do that.

While Jesus teaches about the importance of sin and forgiveness, he also demonstrates in words and actions how important it is to realize we are made in the image of God, and in the first chapter of Genesis, before we hear anything about sin, God pronounces that the creation of humankind is “good – very good.” So Lent is not about beating ourselves up for being such terrible sinners. It’s about recognizing our humanness – that we are God’s beloved, that God forgives us even before we ask for forgiveness, and that we need to accept our worthiness before God, our essential goodness.

However it’s easy to jump to the other extreme and avoid the reality of sin. There is a real struggle between good and evil that is fought in our hearts and wills. And we see all around us in our culture how the battle between good and evil is played out in fantasy and science fiction, in vampire films and computer games.

These stories and games are projections of the battles we fight constantly within ourselves, our families, and our world. We only need to watch the evening news to be aware of the raw evil that unfolds before our eyes, even in our relatively peaceful and civilized Canada to say nothing of what is happening around the world.

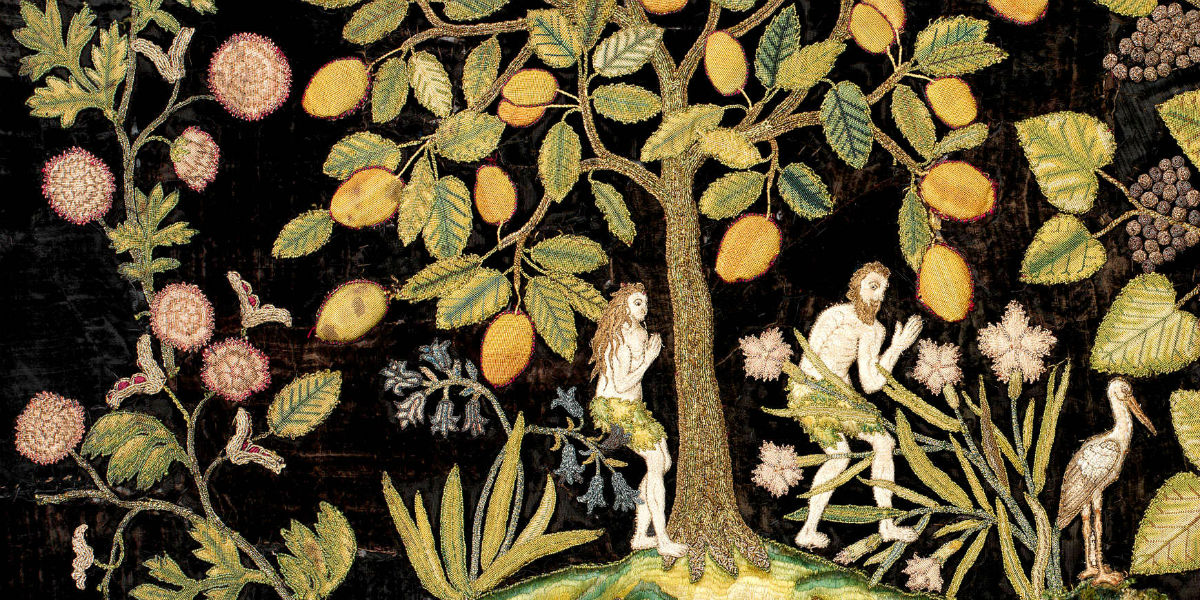

That is why this morning’s passage from Genesis is so important. In that passage, we hear that mysterious and puzzling story about the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Why does God say to Adam and Eve that if they eat the fruit of that tree, they will die? How is it possible that knowing about good and evil can have such disastrous consequences? After all, we teach our children that it is good to distinguish between good and evil. We try to pass on our Christian values, and hope that they will have the wits and the will to make the right choices in life. We teach them what is evil so they can avoid it and choose the good. The scriptures are full of teachings that help us distinguish between good and evil. With this emphasis on discerning and on choosing in our Christian belief and practice, why is it that something we should so highly value is cast, in Genesis, as something so negative? Why is eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil such a bad thing?

I think the point of this story in Genesis is not to teach us to avoid real life and real choices, or to live in some protected, stylized Garden of Eden, some paradise where choice does not exist because there is no evil. The story in Genesis 2 is not meant to say it is bad to know the difference between good and evil and to make choices based on that knowledge.

No, I think the point of this story is about obedience – about listening to God (for that is what the origin of the word obedience means – obedire, “to listen”). Eve and Adam’s sin lay in listening to the serpent rather than God, in allowing the serpent to convince them that it was bad to know good and evil, when in fact God had already created them with the capacity to learn the difference, and to act on it. Ironically, in listening to the serpent, Eve had already made a choice – though a bad one – between good and evil. Had Eve not listened to the serpent, and had Adam not listened to Eve, they would have learned the difference between good and evil in God’s own way, in God’s time. Instead, they took it upon themselves to bypass God’s program.

The story, of course, is saying that this potential to choose badly is present in all of us. It was present in Jesus, insofar as he was human. And so he was subject to temptation like Eve, like Adam, like the rest of us. The difference is that he resisted the temptations in the wilderness.

Now what do these temptations mean?

The temptation to turn stones into bread was a temptation to satisfy Jesus’ bodily needs at a time when fasting was important to sharpen his insight and his ability to hear God. The temptation to throw himself off the pinnacle of the temple was a temptation to power, to enjoy the adulation of the world. The temptation to fall down and worship Satan was the ultimate temptation of the devil – the temptation of apostasy, to deny God in exchange for a lesser good.

These temptations are often associated with the three renunciations we make at the time of our baptism. We are asked to renounce “the powers of the world that corrupt and destroy” – the temptation of the world; to renounce the “sinful desires that draw us from the love of God” – the temptation of the flesh; and to renounce “Satan and the spiritual forces that rebel against God” – the temptation of the devil.

In renouncing evil and choosing good. In doing so, we presume we are capable of distinguishing the difference, of making the right choices. God does indeed – through the Holy Spirit – give us the gift of discernment. But God gives us more than the desire and the will to avoid evil and choose good. God also gives us a challenge – to work actively on the side of good, for the coming of the God’s kingdom. That is what the five promises in the baptismal covenant are about. After we have renounced Satan three times, and turned to God three times, we then make six promises as part of the baptismal covenant:

- to continue in the Apostles’ teaching and fellowship, the breaking of bread and the prayers (in other words, to stay connected to the Body of Christ, the church – to be fed by its teachings and its fellowship of prayer);

- to resist evil and to repent and turn back to God whenever we do sin;

- to proclaim by word and example the good news of God in Christ;

- to seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving your neighbour as ourselves;

- to strive for justice and peace among all people;

- to safeguard the integrity of God’s creation, and respect, sustain and renew the life of the Earth.

In these vows, we take a stand on the side of good, and we reject evil. We acknowledge our weakness and sin, our need of a Saviour, and our desire to give ourselves to helping the world grow in love. In the choices that each of us makes, we enable or obstruct the ability of others to make good choices.

As we travel through Lent, the scripture readings each week will help us go deeper n understanding the meaning of our own baptism and our commitment to be disciples of Jesus – which we will reaffirm at the Great Vigil of Easter. May God bless each of us with the discernment needed to reject evil and embrace the good, wherever and whenever and however we are able.

Lent 2: NIC AND JESUS

Readings: Genesis 12:1-4a; Romans 4:1-5, 13-17; Psalm 121; John 3:1-17

Nicodemus has been hooked by Jesus. He’s been watching him, listening to him, wondering about him. Nic has also heard all kinds of criticism about him from his colleagues – the Pharisees. (I hope you don’t mind me calling him Nic – he has come to seem quite real to me, and Nic just seems too formal for someone I have gotten to know quite well from a spiritual point of view.)

Like the rest of the Pharisees (who were the spiritual leaders of the Jews in Jesus’ time) Nic keeps the Jewish law impeccably – not only the spirit of the law as given by Moses, not only the prescriptions in the book of Leviticus that go way beyond the Ten Commandments in detail and difficulty, but also all the intricate details of the laws that the scribes wrote as commentaries on the laws in Leviticus. Nic was a shining role model among the Pharisees.

And yet something about Jesus caught his attention and wouldn’t let it go. Jesus, who always seemed to be stretching the limits of the law, like healing people on the Sabbath when no work was to be done; Jesus, who liked sharing meals with the ritually impure; Jesus who liked offending the social mores of the day by sleeping on the road with his disciples having no fixed residence; Jesus who told stories that seemed to make outsiders seem more moral than the Pharisees, as in the parable of the Good Samaritan.

We can guess what might have intrigued Nic about Jesus. Maybe he had become a little discouraged or even bored with his job studying the commentaries on commentaries on commentaries about the law. Maybe he was longing for something more fulfilling in his life, something that would light a fire in his heart, not just be fodder for his brain. Maybe he deeply needed real spiritual friendship, the kind that Jesus offered to his disciples. In other words, maybe Nic is having a vocational crisis. Is he meant to be a Pharisee – or a follower of Jesus?

But it’s dangerous to admit this up front, or even to ask too many questions in public – and so he comes to Jesus at night when he is less likely to be noticed by his Pharisee colleagues. And you can hardly blame him. He’s exploring, questioning, maybe even hoping that this Jesus has something better to offer, that he might even be the Messiah. But he doesn’t know yet and so unlike the other disciples he’s more cautious — he doesn’t want to burn his bridges until he knows more about this handsome, charismatic young prophet Jesus.

He says to Jesus, ‘Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God; for no one can do these signs that you do apart from the presence of God.”

With the title “Rabbi” or “teacher” Nic is acknowledging that Jesus has a certain personal and spiritual authority even though he does not have an official place in the establishment. But clearly he knows there is more to Jesus than being a talented Rabbi. He is trying to understand. Like Abram in our first reading from Genesis, he is responding to a call from God to leave the place where he lives – not literally, but in terms of his position and authority – and to go somewhere new, somewhere unknown. It is a spiritual journey Nic sets out on when he comes to see Jesus at night.

And what does Jesus say? “Very truly, I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God without being born from above.” Nic takes this very literally, and asks Jesus how a person can possibly enter into the mother’s womb a second time and be born again.

Jesus responds by trying to explain that he is talking about a spiritual birth – a birth that comes from the Spirit. And he seems amazed that Nic doesn’t understand this. Jesus tries to help him by saying “The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.”

But this just seems more puzzling to Nic. “How can these things be?” he asks. Remember he is a Pharisee, a literalist, and he probably hasn’t had much practice in understanding metaphors. So he just doesn’t get it. “Are you a teacher of Israel, and yet you do not understand these things?” Jesus asks. Well, we might feel the same way as Nic if we went to Jesus and he responded that way.

Nic, like ourselves sometimes, has to get the truth from his head to his heart, to know experientially that the Spirit of God cannot be controlled by us. We have no control over the wind, and even the most talented meteorologists can’t always predict where it’s going to go next. Likewise we have no idea how the Spirit might play in our lives, how God might use us, or what will happen if we respond to God’s call.

Abram couldn’t have predicted how the Spirit would blow through his life, nor could any of our ancestors in the faith, ancient or modern. People like Martin Luther King, like Gandhi, like Mother Teresa – all of them simply responded to God’s call to go on a journey. They blessed more people than the stars in heaven. But they couldn’t have known that ahead of time.

Nor can we. Nor could Jesus. The one thing we do know is that somehow, mysteriously, we have a part in the way God works out the divine purpose. The journey God calls each of us to is a road that leads to the working out of God’s plan, the Kingdom of God.

And that is summed up by gospel writer John. After we have listened to this conversation between Nic and Jesus, we are thrown back on the simple, glorious truth that “God loved the world so much that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life.”

Martin Luther called this short verse “the gospel in miniature.” And indeed, it sums up everything we know about God’s self-giving love, about Jesus’ faithfulness and obedience even to death, about the grace of forgiveness and new life that we receive from this gift of God’s love.

Abraham left his home to go out into a new, unknown world, and died of old age. Jesus followed God’s call for him even though it meant death at a young age. Nic became a follower of Jesus (at least we assume that because he brought Jesus’ expensive myrrh and aloes to anoint Jesus’ body after the crucifixion).

May we have the faith of Abraham, the courage of Nic, and the love of Jesus that allows us to say “yes” to whatever call God puts in our hearts. And may we never forget that God watches over our going out and our coming in, and will make us a blessing to all those whose lives we touch.

Lent 3: TWO WOMEN AND AN ANGEL

Readings: Exodus 17:1-7: Romans 5:1-11: Psalm 95; John 4:5-42

Today is the third Sunday in Lent – we’re about halfway through our Lenten journey. And many years (depending on the date of Easter) the feast of the Annunciation comes very near the middle of Lent. I was thinking about that as I was reflecting on the story of Jesus meeting the Samaritan woman at the well. I began to realize how much the two women have in common. At first glance they seem very different – Mary pure, young, receptive; the unnamed Samaritan woman older, sexually promiscuous, and rejected by her townspeople. Mary was open to God; the unnamed woman someone who seemed to have flaunted God’s laws. Mary was a Jew, the unnamed woman a Samaritan – with a history of cultural antagonism between the two Semitic peoples.

But in spite of their differences, both women are reflected in each of us. Each of us is a Mary, and is called to give birth to God. Each of us is an unnamed foreigner who at sometime in our life has had the experience of being an outcast and meeting God in the midst of rejection and shame. And in the two narratives, both Mary and the Samaritan woman have a profound meeting with God.

Let’s look at Mary first. As far as we know she was an ordinary Jewish peasant girl in an ordinary Jewish family living in the Palestine of the first decade of the Common Era. Then one day she is sitting there minding her own business and her life changes. I say “sitting there” – artists often depict her sitting meditatively doing what we typically think of as women’s work – sewing or spinning or weaving, or just sitting. But she could just as easily be feeding the chickens, helping her mother bake bread, changing diapers on her baby brother or sister, or any number of things that a young girl just past puberty might have been doing in those days.

And then begins an interesting conversation with God through God’s messenger Gabriel. The angel says, “Hello Mary, beautiful and gracious one. The Lord is with you.”

She was perplexed, and pondered what this greeting could possibly mean. Now – we hear a similar greeting every Sunday: “The Lord is with you . . . and also with you.” Do we really grasp what we are saying – that God is with us, in us? That we are spiritually bearers of the image of God, just as Mary was pregnant with the Son of God? If we really think about it, we might be as overwhelmed as Mary to think of the sheer wonder of being God-bearers for each other.

The angel knows what Mary is thinking, and replies, “Don’t be afraid Mary – for God has favoured you and you are going to become pregnant with God’s son, and he will rule over the house of David for ever.” The dialogue continues: “how can this be since I’m a virgin?” Now notice that the angel doesn’t go into the theology or biology of this – the angel just says that the Holy Spirit will cause it to happen, and tells Mary that her cousin Elizabeth, who is old and past childbearing age, has just conceived 6 months earlier.

With all this miraculous news, it’s amazing that Mary says quite calmly, ‘Here am I, the servant of the Lord. Let it be with me according to your word.” And the angel leaves her with this stunning knowledge that she is to bear the Messiah.

And you know the rest of the story. Jesus is born, grows up, starts his public ministry, and then one day he meets a Samaritan woman at the well. And the story of the Annunciation begins all over again, with some important differences.

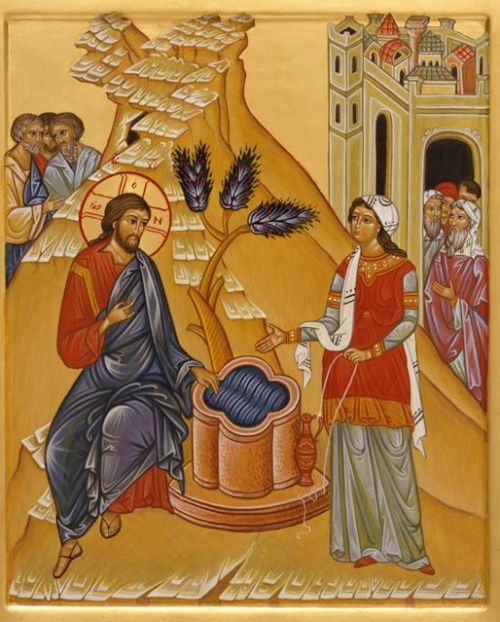

This time it is Jesus who plays the role of the angel – God himself is the messenger of God. He is travelling through Samaria with his disciples, and they have gone off to find some lunch, leaving Jesus, weary and thirsty, sitting at a well – the very well where Jacob, centuries earlier, had met his wife Rachel. By Jesus’ time this had become Samaritan territory, and the Samaritans – though ethnically they were cousins of the Jews – were considered foreigners. While they worshipped the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, they had some major differences with Jewish religious belief – for instance they had their own centre of worship and did not accept Jerusalem as the centre of the spiritual world as the Jews did.

So it was very unusual for a Jew like Jesus to get into a conversation with a Samaritan, and even more unusual with a woman. As a conversational opener, Jesus says simply “give me a drink.” No polite greeting like “Hail Woman of Samaria!” And then she responds – like Mary – with a perplexed question. “Why are you a Jew asking me, a woman of Samaria, for a drink”?

And Jesus – like the angel to Mary – answers with a non-answer. “If you knew the Gift of God that is standing before you, you would ask for Living Water.” In other words, Jesus has asked her for a drink, but if she knew who he was, she would ask him for living water – spiritual water – that would cleanse and heal and restore her.

She seems even more perplexed, but she’s very polite in asking him questions: “Sir” she says, you don’ t have a bucket – how are you going to get living water?” And Jesus answers again quizzically – whoever drinks the water I give will have “a spring of water gushing up to eternal life.”

And the conversation goes on, getting deeper with each exchange, as Jesus shows her more and more of herself, and draws her into a closer relationship with him until, finally, she realizes that he is someone very special – possibly even the Messiah And she goes back to the town and tells everyone, “Come and see the man who has told me everything I have ever done” – and we might add – who has accepted her, forgiven her, made her know that she is beloved and accepted by God.

The townspeople invite Jesus to stay, and at the end of his time in that Samaritan town, the people say to the woman, “It is no longer because of what you said that we believe, for we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this is truly the Saviour of the world.”

This statement is important on many levels – first, it tells us that she has shared the good news of Jesus with the townspeople; second that they have acknowledged him as the Messiah; third, that they will now want to tell others about Jesus; and finally, that she is now accepted by her townspeople. She is no longer the cast-off woman who has had five and more husbands. She is restored to the community.

And something even deeper happens – there is the beginning of reconciliation between the Jews and the Samaritans – not in a political sense, but in the way of relationships. These Samaritans recognize Jesus as the Saviour of the world, the Messiah, and in doing that it no longer matters where they worship God – whether in Jerusalem or on the mountain of their own temple. Because Jesus has said “whoever worships, must worship in Spirit and in Truth.”

In becoming the bearer of Christ to others, the unnamed Samaritan woman has said “Yes” to Jesus and to the truth of who he is, just as Mary said “yes” to the angel.

Although the Samaritan woman had a checkered past, and although Mary was a virgin and naive about men, both women share something important in common. Both of them – the innocent Mary and the forgiven sinner of Samaria – become Bearers of Christ, bearers of the Good News.

And so it is with us. I believe it is when we can accept both our innocence and goodness on the one hand, and our sinfulness and shame on the other, that we can be most truly open to experiencing God’s love, to being reconciled to others, and to spreading that word of hope to others – as both Mary and the Samaritan woman did. When God touches us in that way, we can say “We have heard for ourselves, and we know this is truly the Saviour of the World.” And once we know that for ourselves, we can also say, with Mary, “Here am I the servant of the Lord; let it me with me according to your word.”

Lent 4: COME, LIVE IN THE LIGHT

Readings: 1 Samuel 16:1-13; Psalm 23; Ephesians 5:8-14; John 9:1-41

The readings today are all about light – about walking with God out of darkness into light, shifting our gaze from appearance to reality, turning from untruth to truth. And as we explore that journey, I’m going to ask you to help me by singing a refrain:

Come, live in the light!

Shine with the joy and the love of the Lord.

We are called to be light for the kingdom,

to live in the freedom of the city of God.

I want to start with the psalm because it serves as a reflection on the truth of all the readings. It is undoubtedly the most beloved of all the psalms by people both in and outside the church. And why is that? I think because it helps move us along the path of our life from darkness to light. It gives us hope that there is something greater than the apparent hopelessness and darkness of our world. The psalm invites us to walk through the dark valley out into the light of Christ:

Even more significant, perhaps, is the image of God which the psalm captures – a God who cares for us deeply; who walks with us in light and shadow, in life and death; a God who feeds and nurtures us even when we feel attacked and wounded by life; a God who loves us like a father and a mother; who is the source of our deepest longings; and above all, a God with whom we can live in intimate relationship: “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”

That image of living in God’s house forever reflects something deep in every human soul that longs for God and longs for home – for intimacy and holiness, to live in God’s house, not just visit it. This holy longing to dwell with God is reflected in the other readings this morning – first pointing back in our faith history to the story of Samuel and David, and then looking forward to the light which that sheds on our journey with Jesus:

Come, live in the light! . . .

Samuel is definitely walking through the valley of the shadow of death, feeling depressed and desolate after the disastrous crash of Saul’s reign. And then – in the paraphrase of Eugene Peterson – God said to Samuel “So – how long are you going to mope after Saul? You know I’ve rejected him as king over Israel. Fill your flask with anointing oil and get going.”

Samuel’s mission to bring Saul to his knees has ended, and now, in spite of his fear of Saul, he obeys God and embarks on his new mission – to anoint a new king over Israel. He is beginning the journey from darkness back into light. As he reviews each of Jesse’s sons, he is discerning the voice of the Lord – who has the Lord chosen? It is not the person Samuel or Jesse would have chosen. But as the light of truth shines on David, there is another ray of light – the light of a new mission, a new era for Israel.

God’s choice of David as King catapults us into another journey, a long journey over hundreds of years. David’s star will rise and fall, spectacularly, but God will never abandon him. The Lord is David’s shepherd, and ultimately, through his descendants, brings about the Incarnation and the whole paschal journey of Jesus. The anointing of David – which prepared him for suffering servant leadership – is reminiscent of the anointing of Jesus before his crucifixion. God’s prophets and kings, like Jesus himself, walk through darkness before they emerge into light.

Come, live in the light! . . .

And so we come to Jesus’ encounter with the man born blind. He too had to go on a journey from darkness into light. Like many of the stories in John’s gospel, Jesus’ encounter with this man is extremely complex. It involves not only the man himself and Jesus, but a whole cast of characters – the disciples, the neighbours, the parents, the Pharisees. Everyone except Jesus is blind in one way or another, but only those who are open to the truth of Jesus’ healing are themselves healed of their spiritual blindness.

The story of this unnamed man is also our story – a baptismal journey of being brought out of darkness into light, of dying with Christ in order to be raised with him. In one sense the entire gospel of John can be seen as a commentary on baptism,

On the first Sunday in Lent we hear the account of Jesus’ rejection of Satan from Matthew’s gospel – and then in the following weeks, narratives from John that develop the baptismal theme: Jesus meets Nicodemus at night, challenging him with the need to be born of the Spirit. Jesus meets the Samaritan woman at the well – this time in the full light of noon rather than in darkness – asks her for something to drink and offers her living water. The baptismal mystery deepens as Jesus uses the water of his own spit to make mud to anoint the eyes of the man born blind.

In the early church it was a common practice to anoint the baptismal candidates with the oil of chrism before having them step into the water, or before they had water poured over them. The fact that Jesus uses mud instead of oil is significant of the upside-down values of the kingdom of God. Mud from spit and dirt – that’s about as close to the ground as you can get, and it reminds me of the word humility, which comes from a Latin word humus which means earth or dirt. To be humble is to recognize ourselves as creatures of the earth, to realize that we are creatures, and not the creator, not God.

Just as Adam was made from the dust of the earth, just as we are born from the water of our mothers’ wombs, so this blind man was reborn by coming into intimate contact with body fluids and dirt. And then he steps into the Poor of Siloam and is healed. We might say he “sees the light.” He certainly sees Jesus, the light of the world. The candle which we are given at the end of the baptismal rite is a symbol of that new kind of seeing:

Come, live in the light! . . .

When Jesus is asked by the disciples who sinned that this man was born blind, Jesus answered “neither – he was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him.”

Now in saying this, Jesus was pointing out something about the human condition – we are all physically blind when we start life, and we all have spiritual blindness when we embark on our Christian journey. The blindness is a gift because our very vulnerability, and our humility (that is accepting ourselves as vulnerable creatures and not the Creator) allows us to see truth that we can’t see if we are wise – or think we are. The healing of the man born blind is a sign – almost, we might say, a sacramental act – reflecting the reality that Jesus is the light of the world, and that we come to recognize that light when we accept our need for healing.

Come, live in the light! . . .

And after Jesus’ response that the man’s blindness was not the result of sin – then the real controversy develops. If you follow the dialogue in this narrative, at first it’s almost hard not to laugh at how dense the Pharisees are – especially when they insist on asking the man’s parents if he was really born blind. “Ask him – he is of age – he will speak for himself.” When they ask the man the second time about his healing, he answers simply, with what is entirely obvious: “One thing I know – that once I was blind and now I see.”

When they continue to quiz him – how did this happen, what did he do to you, he responds ironically and says “why do you keep probing? do you also want to be his disciples?” It’s reminiscent of Jesus’ temptations in the desert, and like Jesus, the man born blind holds firm against any attempt to be intimidated by these tempters.

Gradually, then, the conversation becomes darker and more insidious, and begins to sound like a trial. The dialogue comes to a climax when the authorities drive the man out. They are beside themselves with anger because they couldn’t trick him into betraying either Jesus or himself. It is all too reminiscent of Jesus’ trial before the Sanhedrin.

Then all of a sudden things become quiet. Jesus goes to the man and confronts him with the truth. “Do you believe in the Son of Man? and he says “Lord I believe.”

It is a second healing of blindness – the completion of his baptism, if you will. The first healing was physical. The second was spiritual. “I have come into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see, and those who do see may become blind.” Those who reject Jesus not only lead him into a path of darkness toward his crucifixion, but plunge themselves into darkness as well. The simple and the humble on the other hand – like the man born blind and his parents – not only can see but have acquired the light of wisdom, the knowledge of who Jesus is.

Like newborn babies, whose sight comes into focus only gradually, our spiritual sight also gradually comes into focus if we are open to the light of Christ. The man born blind gradually comes to understand who Jesus is – first calling him a prophet, later falling down and worshipping him at the Son of Man.

The more we see, the more we grow in love and compassion, the closer we can follow Jesus, helping to build the Kingdom of God.

Come, live in the light!

Shine with the joy and the love of the Lord.

We are called to be light for the kingdom,

to live in the freedom of the city of God.

Feast of the Annunciation: THE PRINCESS BRIDE

Readings: Isaiah 7:10-14; Hebrews 10:4-10; Ps 40:5-10; Luke 1:26-38

Recently I was watching The Princess Bride – a film from the 1980’s based on book written in the 1970’s which I had never seen. It’s a modern-day fairy tale about a princess who falls in love with a farm boy. On the surface it’s a really good adventure story, funny and heart-rending both. But going deeper, it’s a tale of death-and-resurrection which touches on all the themes of Lent and Holy Week. Although the princess is in love with the farm boy, an evil king tries to force her into a marriage which will consolidate his political power. The farm boy disappears and the word is out that he has been murdered by pirates. The princess awaits her wedding day with grief and horror but also with an unwavering belief that the farm boy will come to her rescue before the dreaded day.

Sure enough, the farm boy turns out not to be dead, and after going through many trials on his way to rescue the princess, he is captured by the king’s men, put into prison, and tortured on a home-made torture machine which sucks the life-breath out of him. Then miraculously he is brought back to life by a benign magician who literally blows the breath of life back into him – with a bellows and a long hose! It can almost be an image of God blowing the breath of life into Adam at creation. The farm boy is a kind of Christ figure, crucified and resurrected almost supernaturally. And he is able to pass on that new life, saving the princess from death-by-marriage, and through his love bring new life to her.

Very interesting, you might say, but what does all this have to do with the Feast of the Annunciation? Well, there is one line near the beginning of the story that really struck me as containing the central message of the Annunciation. Whenever the beautiful young princess asks the farm boy to do something for her, he looks her in the eyes and says simply “As you wish.” “As you wish.” One day, the narrator tells us,

“she was amazed to discover that when he was saying ‘As you wish,’ what he meant was, ‘I love you.’ And even more amazing was the day she realized she truly loved him back.”

“As you wish.” I love you.”

That, in essence, is what Mary said to the Angel of God who came to announce that she was going to become pregnant with Jesus. “Let it be with me according to your will.” “As you wish,” she said. “I love you,” she meant. Mary loved God deeply enough that she could say “yes” to what must surely have seemed a fairy-tale kind of situation.

Jesus would eventually say the same thing in the Garden of Gethsemane: “Not my will but yours be done.” “I love you.” The love had to be there first, or Jesus could never have said, “your will be done.”

And we are called to do the same. Most of us are not called to give up our lives as Jesus did. But we are often called to give up the plans we have for our lives in favour of something greater that God may be calling us to, as Mary did. Our ability to say yes to God, like the farm boy and Mary and Jesus, is only possible when we know we are loved. Then we can respond in love. “As you wish.” “I love you.”

God’s call to each of us is as mysterious as Gabriel’s words to Mary. “She was much perplexed by his words,” Luke tells us, “and pondered what sort of greeting this might be.” As well she might. When an angel comes and tells you that you are favoured, you can be sure not only that you are loved, but that much is going to be demanded of you. To be able to react as Mary did when we feel God calling us to take some new direction, to meet some great challenge, to become instruments of God – to say yes as she did – requires the courage that comes from knowing we are loved.

And we know we are loved because of the evidence we see in the Incarnation – in God choosing to come and live among us. The Annunciation is actually the first chapter in that story. And in “humbling himself to share our humanity,” as we read in Philippians, God changed the rules of the game. Instead of our needing to bring sacrifices to God, or other rituals of cleansing, God simply asks that we follow Jesus’ example of obedience, that we learn to say “as you wish,” “your will be done.” The writer of the letter to the Hebrews quotes from Psalm 40 which we just sang, and describes Christ speaking to God in these words:

“You have not desired or taken pleasure in sacrifices and burnt offerings and sin offerings”; then he added, “See, I have come to do your will.”

Rather than the ceremonial sacrifices of the Old Testament, Jesus does away with sin and death by being obedient to God. Because the human Jesus knows how deeply he is loved by God, he is able to say, “See, I have come to do your will.” “I love you.” Jesus can say yes to God – “I love you” – because he has first known God’s love. The same was true of Mary.

And that is what God asks of us: to respond to God’s love for us by saying “As you wish”; “I have come to do your will” ‘Let it be with me according to your will.” “I love you.” They all mean the same thing.

And so it’s really appropriate that we celebrate the Feast of the Annunciation just before Holy Week. God became human like us. His mother was a humble peasant girl. He was born and brought up in a human family, with an adopted father who was a carpenter. He got into political trouble with the religious authorities because they didn’t like his preaching God’s love rather than the need for sacrifice. He was tortured and killed. And he rose again. All because Mary chose to say “Yes,” Here am I the servant of the Lord.” And all because Jesus said, “not my will but yours be done.”

As you wish. I love you.

Lent 5: DEAD OR ALIVE?

Readings: Ezekiel 37.1-14; Psalm 130; Romans 8.6-11; John 11.1-45

We have two very powerful stories in the readings this morning. Both of them are a little gruesome, even creepy – a valley of dry bones, and a dead man who walks out of his tomb, smelling of death and with the grave clothes still wrapped around him. But both of them are about new life, and they fit perfectly into the pattern of readings we have had over these five weeks of Lent. Think of them as part of a Biblical miniseries preparing us for baptism which in turn prepares us for Easter.

Baptism is a sacrament of death and rebirth – we symbolically die to our sin and are reborn as followers of Jesus. And all these readings in our Lenten miniseries develop this baptismal theme. On the first Sunday in Lent we heard the account of Jesus’ temptations in the desert and how he rejected Satan. That is the very first thing we do in the baptismal service — to renounce Satan and all evil powers.

Our miniseries has developed over these past few weeks in a series of narratives from John’s gospel that talk about death and new life using the symbols of water and light. On the second Sunday of Lent, we heard about Jesus meeting Nicodemus at night, challenging him with the need to be born of the Spirit, to come out of the darkness into the light. The third week we heard the story of Jesus meeting the Samaritan woman at the well – this time in the full light of noon rather than in darkness. He asked her for something to drink, which she gave him, and then he offered her living water. It was her baptism. On the fourth Sunday in Lent the baptismal mystery deepened as Jesus used the water of his own spit to make mud to anoint the eyes of the man born blind and then has him wash in the Pool of Siloam.

This whole sequence of readings reflects our own story of being brought out of darkness into light, of dying with Christ in order to be raised with him. And our two stories today develop that theme further.

The reading from Ezekiel is a highly symbolic account of a vision God gives to Ezekiel to encourage the people of Israel after a devastating time in their history. They had been through a period of terrible wars, the temple had been demolished, the city of Jerusalem destroyed, and like many wars of our own time, all that was visible on the battlefield was a pile of bodies and bones. We have seen photos like that of the Holocaust, and we’ve seen pictures of mass destruction more recent than that. It’s almost as if Ezekiel the prophet could see thousands of years into the future, to our own time, and offer us a vision of hope.

Ezekiel looked down into the valley of dry bones and God said to him, “Prophecy. Say to these bones, “O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord.” And the bones came together. Then God instructed Ezekiel to say to the wind, “breathe upon these slain and they shall live.”

Each action in this dream-vision occurs by Ezekiel speaking the Word of God, literally. In commanding the bones and the wind to behave as God has instructed, he brings about their rebirth. It reminds me of the story of creation in the Book of Genesis, where God speaks each part of creation into being. God said “let there be light” and there was light. God said “let vegetation appear on the earth” and it did. God said “let us create humankind in our image” and it was done. The Word of God is powerful, creating a new world, and breathing new life into the dry bones of Ezekiel’s vision. The same Word speaks life into us at the time of our baptism when the priest says, “I baptize you in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.” And God’s word speaks new life to us whenever we are willing to die in order to be reborn, to die to sin and selfishness and to be reborn in love and compassion. When we turn away from all that keeps us from God, God gives us the grace we need to grow in love for ourselves and through acceptance of ourselves, we grow in love and compassion and acceptance of others.

This spoken Word, this commanding Word of God, is equally powerful in the narrative of Lazarus.

Jesus receives a message from Mary and Martha that his friend Lazarus – their brother – is on his death bed. Instead of going immediately to see Lazarus and healing him as he has so many others in the gospel stories, Jesus tells the disciples that this is all happening “so that the Son of God may be glorified through it.” And so he waits two days before going to the home of Lazarus, Mary and Martha in Bethany, near Jerusalem.

The disciples are agitated and don’t want Jesus to go because they suspect he will run into trouble in Jerusalem – the local people are threatened by his message and have already tried to stone him. The disciples heard Jesus say that Lazarus was asleep, and they take him literally – “Lord if he’s fallen asleep he will be alright” – in other words, you don’t really have to go. But Jesus says plainly that Lazarus has died, and Jesus is glad he wasn’t there to heal him because now he is going to do something greater.

When they arrive, Jesus is met by Martha, who says what the disciples must also have thought – if Jesus had come while Lazarus was still alive, he might not have died. And then follows this amazing dialogue between them, with two of the strongest statements of faith anywhere in scripture. Jesus says to Martha “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” It sounds like the questions we are asked at baptism: Do you believe in God the Father? Do you believe in Jesus Christ the Son of God? And we answer “I believe” – just as Martha answers “Yes Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.”

Other people in our miniseries have also professed their faith about Jesus. The Samaritan woman at the well and the townspeople recognized Jesus as the Messiah, the Saviour of the World. The man born blind confessed that Jesus was the Son of Man – another way of saying he was the Messiah. And now Martha also recognizes him and professes that he is the Messiah, the Son of God.

When Martha goes to find her sister Mary, Mary repeats Martha’s accusation: “Lord if you had been here my brother would not have died.” She is weeping, the townspeople are weeping, and Jesus himself begins to weep and John tells us, is “greatly disturbed in spirit.” It’s as if the conversation with Martha, which was about belief and faith, is over and now Jesus is entering into the full emotion of the event. A close friend of his has died and even though he is going to be raised to new life, Jesus shows his humanness in the way he expresses his grief.

And then Jesus prayed to God and “he cried with a loud voice, ‘Lazarus, come out!’” Like Ezekiel, commanding the bones to come together, commanding the breath to come into the dead bodies, Jesus speaks Lazarus into life. “Lazarus, come out!”

And when Lazarus comes out of the tomb, Jesus tells the people to unbind him. This is a powerful symbol for all of us whenever we come out of a time of death in our lives – whether spiritual death or severe physical, mental or emotional suffering – into new life. We are unbound. We are free to become more fully the person God desires us to be. All of you have either experienced or have friends who have experienced healing from addiction or anxiety or depression or serious physical illness – or perhaps physical freedom after being in prison.

A great army of living, breathing people emerged from the mass grave of Ezekiel’s vision, with new flesh and new spirit – it is a vision of the whole human race bound together in the love of God. The picture of Lazarus stepping out of his prison of death into the community of his friends and family is a vision of our own personal rebirth into glorious new life. That is the promise of our baptism, and the new life that flows from it. We must first die to all that keeps us away from God. We are like seeds that must be buried in the darkness of the ground before they can germinate and develop shoots. We have to experience death before new life, the sadness of Holy Week before the glory of Easter.

And we approach Holy Week soon. Next Sunday is Palm Sunday, when we will celebrate Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem and begin our re-enactment of the drama of Jesus’ self-giving love which unfolds during our worship in Holy Week. The readings today about Ezekiel’s vision and the freeing of Lazarus are a foretaste of the even more glorious resurrection of our Lord. Thanks be to God.