By Sr. Constance Joanna, SSJD.

Readings: Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12; Psalm 22:22-30; Hebrews 4:14-16; 5:7-9; John 19:1-42

One of my favourite musical compositions is Handel’s Messiah – a universally-loved oratorio in the Christian world as well as among people of other faiths and none. It encompasses the whole of the Incarnation – from Advent through to the Resurrection and the final consummation of creation. It also encompasses the whole range of human emotion as we express our often contradictory feelings of joy and sorrow, of celebration and mourning, at the events of Jesus’ life and ours.

One of the most beloved choruses in Messiah expresses these ambivalent feelings in the words from Isaiah that we just heard read:

“All we like sheep have gone astray. We have turned everyone to our own way. And the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.”

The first part is in a major key, rather bouncy, full of life and joy. I visualize all those sheep who have gone astray romping through the fields, enjoying their AWOL experience. But then the second part, “and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all,” shifts into a somber mood.

To write that chorus Handel would have to have known in his own spiritual experience what it was like to meet Jesus the shepherd, to be saved from the folly of his own wandering away from the fold. Otherwise he might not have captured the spiritual ambiguity in his composition.

That ambivalence between the crucifixion and our own joyful experience of Jesus’ friendship is reflected in the servant song from Isaiah:

Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases . . .

Upon his was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray; we have all turned to our own way,

and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all.

And then it goes on later in the passage to express praise and thanksgiving:

“From you comes my praise in the great congregation;

my vows I will pay before those who fear him. The poor shall eat and be satisfied;

those who seek him shall praise the Lord. May your hearts live forever.

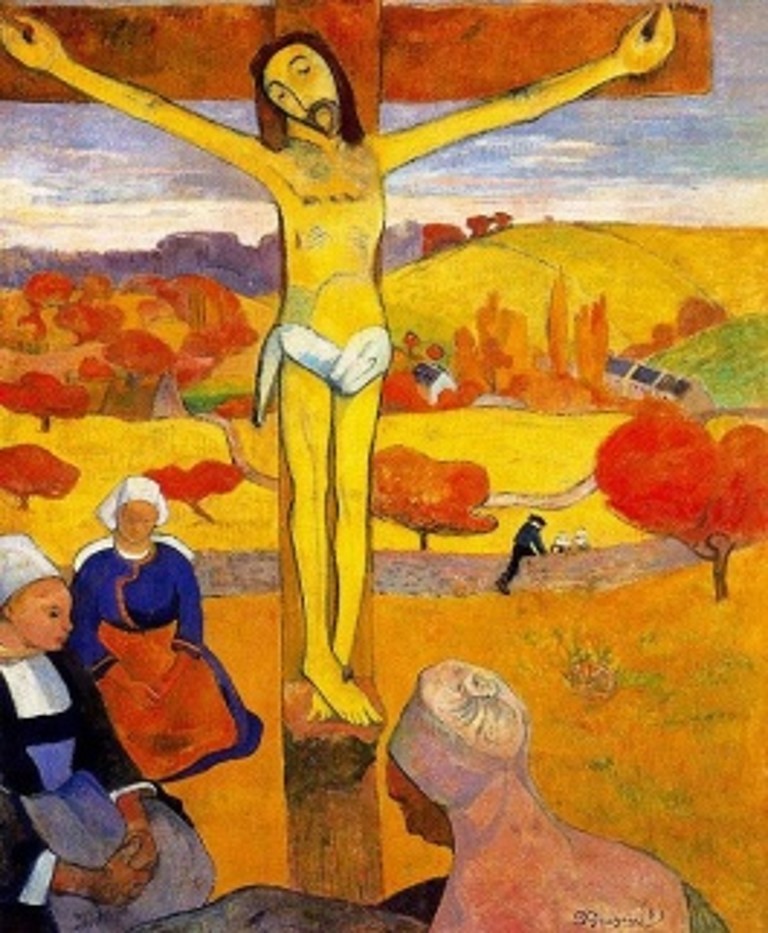

That mixture of feelings is also reflected in the amazing painting of Paul Gauguin which he titles “The Yellow Christ.” Look at the cover of your leaflet. There are layers of meaning in this composition, which presents a shockingly bright picture of Jesus on the cross in a 19th-century Breton landscape, which resembles our own southern Ontario landscape much more than a first-century Palestinian one.

We who gaze at the painting look through the lens of our own experience toward the Breton women at the foot of the cross. Unlike many more traditional paintings of the crucifixion where the women are looking up at Jesus or looking at each other, here they are looking down, contemplatively, seemingly peaceful in prayer. Even Jesus seems peaceful rather than in agony.

In the distance, on the other side of what looks like a low wall or hedge, is a man climbing over it and two other figures there as well – might it be the disciples who ran away? or simply passers-by who, as in one of the Servant Songs of Isaiah, ignored the cosmic significance of the event in the foreground?

Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by?

Look and see if there is any sorrow like my sorrow.

It’s a beautiful fall scene, creating a strange dissonance with the crucifixion. The yellow, as with all the paintings we’re focussing on during this Holy Week, signifies hope and new life – the yellow of the rising sun – even as the trees seem to create a sense of autumn and a landscape changing to reflect the coming winter. The blue sky with a hint of sun on the left side is overshadowed by gathering clouds above. In spite of that, the women in the foreground and those in the mid-ground have no idea of the significance of what is happening. So with our own time and place.

At St. George’s Anglican Church on Yonge Street, where I sometimes assist, we have the lighting of the new fire on Easter eve just outside the church entrance on Yonge Street, at the top of the stairs leading from the street. During the summer we sometimes have the early Eucharist out there, as a deliberate witness to the neighbourhood that Christ-worshippers are still present in our increasingly secular society. Even with the great fire we build for the Vigil, it’s amazing how many people walk up and down the street paying no attention – parents with children, the elderly people from the retirement home across the street with their walkers and canes, individuals hurrying from one place to another, people coming and going from the Metro supermarket. Every once in awhile someone will come up the few stairs and join us, but it’s rare. We just keep witnessing to the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus by doing what Anglicans love to do – public liturgy, the work of the people of God. And we pray for all who pass by, and welcome those who might tentatively join us.

In churches where the crucifix is the focus behind the altar, rather than an empty cross, that same witness is made public. It reminds us of God’s loving emptying of Godself to become a human being, obedient to death on the cross. And that, I believe, is what we need to do in this time when Christianity and other religions are being both ignored and persecuted – to continue being open about our faith and witness to it following Jesus’ new commandment, to love one another and serve God’s people.

Gauguin complained in one of his letters that the impressionist painters before him were concerned only with light and colour, and often missed the spiritual meaning of the world they were painting. That’s not true of all of them of course. But Gauguin was a pioneer at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, introducing the symbolist movement in painting. Instead of graceful, subtle brush strokes of the impressionists, Gauguin uses an almost primitive, bold, and symbolic way of presenting the scene, with strong lines, bright colours, and often figures without clearly distinguishable faces, as with the Breton women in the foreground. Like an icon, every detail of composition, line, shape and colour has an inner spiritual meaning. It’s not meant to be realistic. In fact I wonder whether the Breton women were meant to represent more than people in dress of that time and place. Given their contemplative pose and their own seeming unawareness that Jesus is on the cross, perhaps they represent people of the time in meditation on scripture – rather like an Ignatian gospel contemplation – and the contemplative yellow Christ is part of the vision they are having rather than actually being planted in the autumn landscape of Brittany.

One of the strongest symbols in the painting, which captures the essence of today’s liturgy, is the yellow Christ. Notice that his body is separated from the surrounding landscape by strong outlines – because the colours themselves are nearly identical. The yellow Jesus may mean many things to many people, and you will see it through the lens of your own experience. But for me it is a sign that Christ’s passion – in fact his whole life – is for the entire world, the entire cosmos. As John’s gospel tells it,

God loved the world so much that God gave the only son, that whoever believes in him will not perish but have everlasting life. God did not send the son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through him might be saved. (John 3.16-17)

Notice that John does not say God sent the Son to the church, which is how we often treat that passage. God sent the son for the healing and salvation of the entire cosmos. We are his body, and as part of his body we are sent into the world, to offer our lives for the life of the world. And so it’s significant that Jesus’ body – God’s incarnate body – is one with the landscape and yet in outline distinct from it.

As we reverence the cross today, and receive the body and blood of Christ at communion, let’s always remember that we are called to be God’s body and to share the love of Jesus. There is no other reason to do what we do.