The Rev. Frances Drolet-Smith, Oblate SSJD

In my first year in seminary at Huron College, we had a prescribed course that was dreaded by most of us: Philosophy of Religion taught by our Dean who, in the first class asked us why we were there – what we believed. So haltingly, we each told him in turn, and then he said, “So, you really believe all this stuff. Why?” And we spent that whole term trying to explain ourselves. And lots of times it sounded like foolishness and most of us experienced some sort of a crisis of faith. I lived next door to the Dean, in a semi-detached house, and one evening I went to him, much like Nicodemus, and I said, “I don’t get it”. And he introduced me to Soren Kierkegaard. Now, I didn’t always get Kierkegaard either, but what I did get, I loved! for Kierkegaard put into words things I had been wrestling with, things I didn’t even know I was wrestling with. He wrote:

“Christianity has taken a giant stride into the absurd,” and elsewhere: “Remove from Christianity its ability to shock, and it is altogether destroyed. It then becomes a tiny superficial thing, capable neither of inflicting deep wounds – nor of healing them.”

What I “got” most was that it didn’t need to make sense all of the time: there are some things about this faith of ours that are absurd, and yet, at the same time, that make all the sense in the world. Who knew that was even possible??Kierkegaard spoke of the “leap of faith” and I’ll admit that some times that is precisely what I have needed to do. But thanks be to God, it has not been a leap into the abyss – it has been and is yet at times, a leap into those arms once outstretched upon a cross.

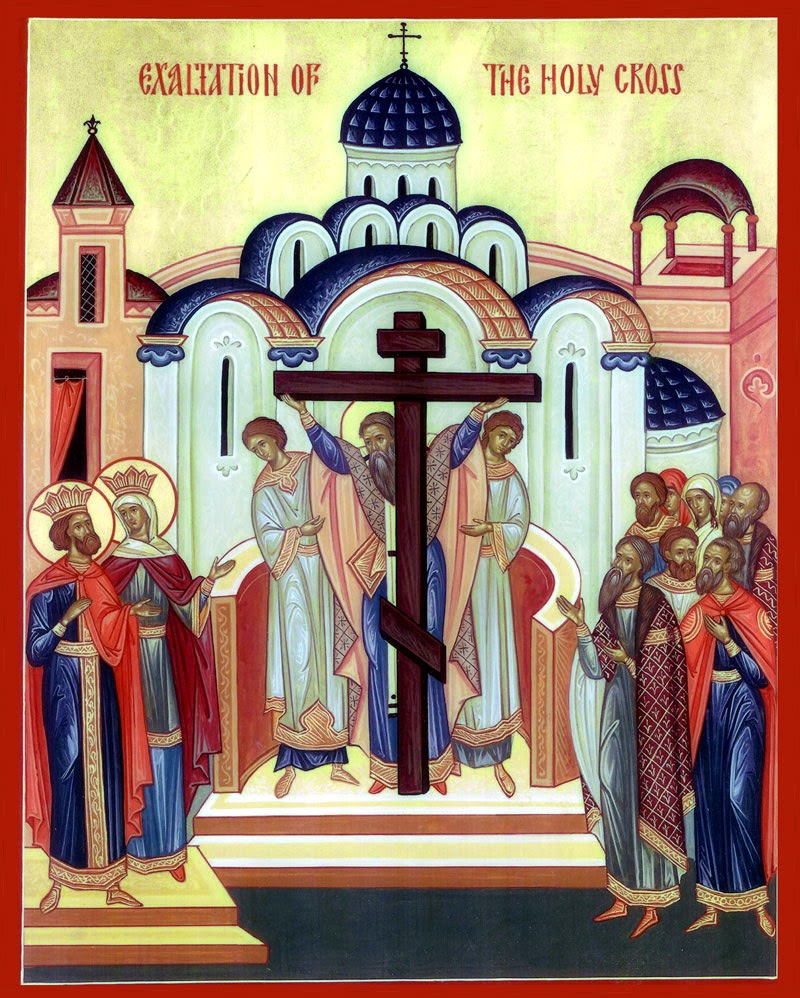

It was early in the 4th century, when Constantine took the Church under his protective wing, that he ordered a splendid church be built at Golgotha, the place where Jesus had been crucified. During the excavation, the workers unearthed a large beam, believed to be part of the cross. The church has become a shrine – a place of pilgrimage. It was dedicated in honour of the Resurrection on September 14 in 335, the day since kept by Christians, both east and west, as Holy Cross Day.

It’s really too bad that when the lections for today were chosen that they didn’t begin at the beginning of the third chapter of John, instead of starting us off at verse 13. The wonderful teaching we heard just moments ago is actually Jesus’ response to a man named Nicodemus – a Pharisee, a leader of the Jews who comes to Jesus by night to ask him how is he able to do the things he does. He makes an albeit tentative assertion about Jesus: “we know you are a teacher who has come from God.” What follows is a lively conversation between two teachers. Now, I think Kierkegaard would have found Nicodemus engaging – imagine their tête á tête! Jesus tells him that “no one can see the kingdom of God without being born from above”. And Nicodemus, incredulous, asks “but how can these things be?” He is challenged by the logic presented and yet finds it compelling enough to stay and listen. He recognizes in this Jesus the very presence of God.

Why are we here? I don’t mean just in this place of prayer and hospitality. I mean why are we here, preparing to make Eucharist? Why do we come – and many of us, often?

We are here because we said “yes” – “yes” to an invitation to be in relationship with this man of the cross, to be in relationship with others who think and feel as we do, to be co-creators with the God who has made us and claims us. We have caught a glimpse of something that makes us better, something that makes us whole, something that makes us holy. We are here because some healing has taken place in our lives. Like Nicodemus, we are here with our wounds and our doubts. But most of all, (and we may not be able to fully explain it), we are here because we have recognized in this Jesus the “One who has come from God”; the One whose life, and teaching, and death – and resurrection has touched us in so profound a way that we are compelled to follow, even to a place that challenges us to wrestle with the very absurdity we sometimes encounter.

We are here because of our baptism. We claim to have been born again of water and Spirit. We speak of what we know and testify to what we have seen: we’re here because we say we believe what some call “the Gospel in miniature”: that God so loved the world . . . We are here because of the Cross. It reminds us of who we are as followers of Jesus Christ. It reminds us of the pain of the crucifixion, the cost of discipleship – and also, thanks be to God, the hope of the resurrection.

Barbara Brown Taylor, in her book “The Preaching Life“, when writing about vocation, wonders what the impact might be if when we were baptized we had been marked with the sign of the cross, “not with water, but with permanent ink – a nice deep purple,” she suggests, “so that all who bore Christ’s mark bore it openly, visibly for the rest of their lives.”

She continues her commentary by speaking about the difference between the ministry of the baptized and the ministry of those who make further vows, in this case the ordained, but I think it is easily extended to monastics, and also to those who make specific vocational promises – such as associates and oblates of religious communities. The ordained [the religious, oblates, associates] she says, “consent to be visible in a way that the rest of the baptized do not. They agree to let people look at them as they struggle with their own baptismal vows.” She further comments that the tasks we commit ourselves to in baptism are in fact the tasks of all the baptized but that not everyone comes under such scrutiny. The part of her writing that most attracts me is that in baptism, we consent to be visible. We, with her, have consented to be visible.

A few days ago, we marked a significant anniversary – not an anniversary steeped in celebration and pride but rather the 23rd anniversary of a day in our lives when the unthinkable happened, a day many of us watched in incredulous horror as planes and people and eventually, buildings fell from the sky and blanketed the city of New York, and indeed the whole world, with ash and sorrow, fear and profound despair. That day set into motion a sequence of events that we are still crawling out from under. Many asked, “Where was God?” In the minutes and hours that turned into days and weeks, and now years, we saw images we cannot and should not forget; images of death – images too of resurrection.

Fr. Mychal Judge, a Franciscan friar, was serving as a chaplain to the NYC Fire Department on that brilliantly sunny Tuesday morning. Michael Ford, author of a biography of Fr. Mychal, was particularly moved by a Reuter’s newspaper photo that you may recall seeing and which has become something of an icon of the tragedy: a photo of the body of Fr. Mychal being carried out of the Tower by 5 rescue workers. Mychal had been inside giving last rites to those killed, when he himself succumbed to the falling debris. Michael Ford described the photo as reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Pieta. He had this to say of it: “There is a great sense of a crucified figure being held by these rescue workers, just as Mary had held the body of her Son at the foot of the cross.” Mychal Judge was no saint: although there is a movement in the Roman Catholic Church to have him declared so. Those who knew him best say he was in fact a very human person with flaws and shortcomings which he recognized and sought to live out of – “an earthy person with wounds”, Ford describes him, “a man who dared to be himself”. He was a recovering alcoholic, he suffered from depression, he struggled with Catholic guilt and his sexual orientation. His ministry was, says Ford, “enriched by his wounds – he had a tangible sense of the suffering within himself: he ministered from the inside, out”. Fr. Mychal was not only a Fire Dept. chaplain; he also worked in homeless shelters and on the street, with drug addicts and those living with AIDS. And he did so because he “spoke of what he knew and testified to what he had seen” – that God does indeed so love the world that he gave his only Son, so that whoever believes in him may not perish but have eternal life. In the midst of suffering and pain and misery, Mychal had found life. He had hope. He shared it with others. He consented to be visible. And a photograph of his broken body carried by those who loved him, forever captures in time the cost of following a crucified, and risen, Lord.

Is all this foolishness? It’s not rational – it’s like falling in love: who can explain it? We have fallen in love with the One who calls us to deny ourselves, to take up our cross, to follow where, if we really thought about it, we’d perhaps rather not go. Places that may wound us, and frighten us, places where we might even lose our lives. Places where, like Nicodemus, Kierkegaard, Fr. Mychal – we in fact, gain everything.

For God indeed so loves this world. . .

It’s true: “Christianity has taken a giant stride into the absurd,” God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength. And, so, for all of that, thanks be to God!