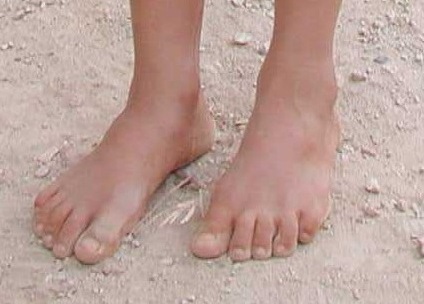

God said to Moses, “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.“ (Exodus 3:5)

The story of Moses and the burning bush in Exodus 3 has always fascinated me. As I was reflecting on it recently, it struck me as a kind of parable of Christian vocation, a parable that has much to say about God’s call to holiness for each of us—about God’s call to each Christian, about God’s call to some to live in monastic communities, and about the role of the monastic life in the church as a whole.

The story of Moses and the burning bush in Exodus 3 has always fascinated me. As I was reflecting on it recently, it struck me as a kind of parable of Christian vocation, a parable that has much to say about God’s call to holiness for each of us—about God’s call to each Christian, about God’s call to some to live in monastic communities, and about the role of the monastic life in the church as a whole.

What intrigues me most about this story is not the burning bush, the bush that burns without ever being consumed. That is fascinating, of course, and a powerful image of the inexhaustible loving energy of God. But what is even more striking is Moses being asked to go barefoot. We tend to think of holiness as something that separates—that makes God seem very far off and quite removed from the dust of everyday living. We might be less surprised if God had asked Moses to put his shoes on.

Instead, God invites Moses to get closer—not closer to the bush, but closer to the very earth on which the fire is burning. Although Moses is initially frightened, the holy ground is a way of connecting him with God, of giving the two of them a space in which to communicate.

To be sure, God’s holiness also demands separation. In all religions, the form God takes both reveals and veils the divine reality. In all the confrontations between God and Moses, God allows Moses to see only so much—fire and cloud, or thunder and lightening or, in one instance, God’s backside—all very concrete, earthy images. Even the person of Jesus both reveals and veils God. We can see only so much with the limited sight we have, and between the burning bush and the promised land stands much suffering in the wilderness.

But Moses’ bare feet remind us that we are called to approach the throne of God with boldness, knowing that God’s holiness draws us into closer communion with our creator, rather than scaring us off.

Each of us, as a Christian, is called to holiness. Jesus said, “be perfect, even as your creator is perfect.” To be perfect, to be holy is not to fulfill some arbitrary moral code. It is to become most fully who we are created to be, to fulfill the unique destiny with which God has gifted each of us. That requires a life-long journey that is best undertaken barefoot, so to speak, with our feet on the ground. It means that we must frequently go off to pray, to be alone with God and our deepest inner selves. But it also means that we must participate fully in the dust and grime of daily life.

Once Moses takes off his shoes, God tells him that he is the one chosen to go to Pharoah to rescue the Israelites from their suffering in Egypt. Moses is understandably nervous, feels extremely inadequate, and says to God, “but who am I to be doing this?” That is a universal human question–who am I? And the only answer to that question, for any of us, is the answer God gives Moses—which is to say who God is. Tell the Egyptians, God says, that “I am—Yahweh—has sent you to them.” Who we are is who we are in relationship to God and to God’s creation.

Monastic communities take a kind of a barefoot approach to living the Christian life, paring away whatever seems superfluous, trying to live by the essentials, to live as closely as possible in relationship to God and each other, and to the creation we are part of. St. Benedict called the monastic life a “school of the Lord’s service,” a “school of love,” or, we might say, a school of holiness. Monks are men and women who are students of the Christian life, who are not better or closer to holiness than other Christians, but who respond to a call to live as a model of what Christian community can be, remembering always that community is dynamic, that its members are in the process of growing and becoming more what God wants us to be—they not live in a utopian form of human society without problems or tensions.

Many monastic communities, including my own, give people a chance to engage that robust kind of community living for a temporary period in their lives. The SSJD Companions program is one of those opportunities to go away for awhile and get a new perspective on our Christian journey. The purpose of all such opportunities can perhaps best be summed up by the famous American writer of the 19th century, Henry David Thoreau, spent two years living in a cabin by Walden Pond in rural Massachusetts. His purpose, he said, was “to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

“Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.“

The Rev. Sr. Constance Joanna Gefvert is Vocations Coordinator for the Sisterhood of St. John the Divine, an Anglican priest in the Diocese of Toronto, and an adjunct faculty member at Wycliffe College, Toronto School of Theology.