St. Theodore of Canterbury, May 4, 2025

Sr. Constance Joanna, SSJD

John 21.1-19: “Do you love me? Feed my sheep”

What do you see at the front of the church when you first walk in?

What most catches you eye?

I grew up in the Methodist Church in the USA, back in the 1950s, when the Methodists were like low-church Anglicans, rather staid and proper with everything done in good order. The ladies wore hats and gloves, even in hot weather. The men wore suits and ties, even in hot weather. Our colonial-style Methodist Church had lovely choir pews at the front, with the altar behind them, like many Anglican churches. It was for me a place of safety, kindness, stability. The hymns and other music were measured, often joyful, like “Joyful, joyful we adore thee.” Sometimes they quiet and contemplative, filling the soul with a sense of God’s presence, like “Jesus thou joy of loving hearts.” And people – of course we saw lots of people (unlike Anglicans the Methodists tended to sit in the front!).

During this time, I had the opportunity to visit some evangelical churches – what my Sunday School teacher called happy-clappy. They were full of energy, and everyone made a joyful noise to the Lord whether they sung in key or not. Those churches always had an open Bible on the table at the front of the church, and I remember asking my Methodist minister one day why we didn’t have an open Bible on our altar. Because, he said, we don’t worship the Bible. We worship Jesus whom the Bible tells us about.

It’s interesting how little things like what you have at the front of your church can convey so much about what you believe is most important. And the symbols change in their meaning over the years.

For instance Anglican churches traditionally had the national flag at the front of the church (more recently at the back of the church), and that’s true of many other denominations as well. It was there to remind us to pray for our country. But in some places of our world, a political party can make the national flag a symbol of the party rather than of the values of the country, something we sadly see south of the border.

But there are two symbols you can find at the front of almost every church – the altar or table, and the cross. The cross of course is a symbol of Jesus’ radical loving sacrifice for us. The table is a symbol of our post-resurrection life, when fellowship with Jesus, and with those who gather in his name, are the new relationships God has called us into.

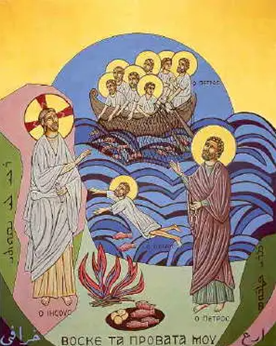

I recently read a sermon by Diana Butler-Bass, a well-known preacher in the USA, who pointed out that after the resurrection Jesus almost always met his disciples at a meal, around a table – or as in this morning’s reading from John’s gospel, at a barbeque. He never meets them at the cross and he never took them back to any of the scenes of his passion

Before I read Diana’s sermon, I had never noticed that. She calls the Last Supper which we celebrate on Maundy Thursday “the first feast of the new Kingdom of God,” and it is followed after the resurrection by other holy meals.

Think of the gospel narratives we read in this Easter season. Jesus meets two of the disciples on the road to their home in Emmaus, on Easter afternoon, and they don’t recognize him until he breaks bread with them. He appears to the disciples in the upper room in Jerusalem on Easter evening, when Thomas is not there. He appears to them again in the upper room a week later, this time with Thomas there

And perhaps most moving of all is Jesus’ appearance on the lakeshore, cooking a fish barbeque for the disciples’ breakfast. Until this point, Jesus had always been a guest at the meals he shared with his friends – both while he was away and in the post-resurrection stories. But this time he is the host. He invites them to eat with him. He must already have done his own fishing because the smell of the cooking fish catches the disciples’ attention.

This interaction is different from the other post-resurrection stories for two other reasons as well. The other appearances seem to be aimed at assuring his friends he is still alive, to know they can still depend on his peace which he shares with them. But in this event in John’s gospel a lot more is going on. For one thing, he helps them fish – in other words, he helps them get back to their traditional calling, giving them a renewed sense of purpose and a new direction after their grieving. For another thing, Jesus forgives Peter for his denial and sets an example for the whole band of disciples of forgiveness and reconciliation.

What does this mean for us?

Perhaps most importantly, to know that we, like Peter, are forgiven of all our denials and betrayals – even the seemingly little ones – when we have not stood up to a bully or defended someone being belittled, or walked by a homeless person without making eye contact, or ignoring the need of a friend because we’re just too busy or getting drawn down the rabbit hole on social media or the internet. We’re just human, we sin, we betray our own values, and we are forgiven just as Jesus forgave Peter.

The meeting of Jesus with Peter has another meaning for us – that being forgiven ourselves, we are called to forgive and work for reconciliation – whether in our personal lives or being advocates for justice in the wider society.

And then if you really take this reading to heart, you will know that your love for Jesus – which is called out by his love for you – means your turning around and loving and caring for other people the way Jesus did.

I remember an old Sunday School song that stops short of the message of this morning’s gospel narrative. It goes like this (if you know it, sing along):

Hey kids do you love Jesus,

Yes, I love Jesus,

Are you sure you love Jesus?

Very sure I love Jesus,

Tell me why do you love Jesus?

This is why I love Jesus,

Because he first loved me.

Oh how I love Jesus,

Oh how I love Jesus,

Oh how I love Jesus,

Because he first loved me.

The same message comes through in other children’s songs, like “Jesus loves me.” There’s nothing wrong with knowing Jesus loves you and longs for you to love him. But love is a verb as we say – an active state of doing, not just being. It’s not necessarily having loving feelings but about an active love that goes out to care for others in the way Jesus did and the way he expects us to do.

Every time Jesus asks Peter “Do you love me?” and Peter answers “Lord you know I love you,” Jesus responds with “Feed my sheep.”

I had the pleasure of being at your Monks Cell Dinner last night. I think this is a great example of St. Theodore’s commitment to reach out to others, to share a meal, to offer hospitality in the way Jesus did both before his death and after the resurrection.

Here at St. John’s Convent we sometimes use the Celtic liturgy for Holy Communion from the Iona Community in Scotland. The words of invitation to communion in this liturgy are a fitting invitation for us this morning:

He was always the guest.

In the homes of Peter and Jairus, Martha and Mary, Joanna and Susanna, he was always the guest.

At the meals tables of the wealthy where he pled the case for the poor,

he was always the guest.

But here, at this table, he is the host.

Those who wish to service him

must first be served by him,

those who want to follow him

must first be fed by him,

those who would wash his feet

must first let him make them clean.

For this is the table where God intends us to be nourished;

this is the time when Christ can make us new.

So come, you who hunger and thirst

for a deeper faith, for a better life, for a fairer world.

Jesus Christ, who has sat at our tables,

now invites us to be guests at his.