By the Rev David Brinton.

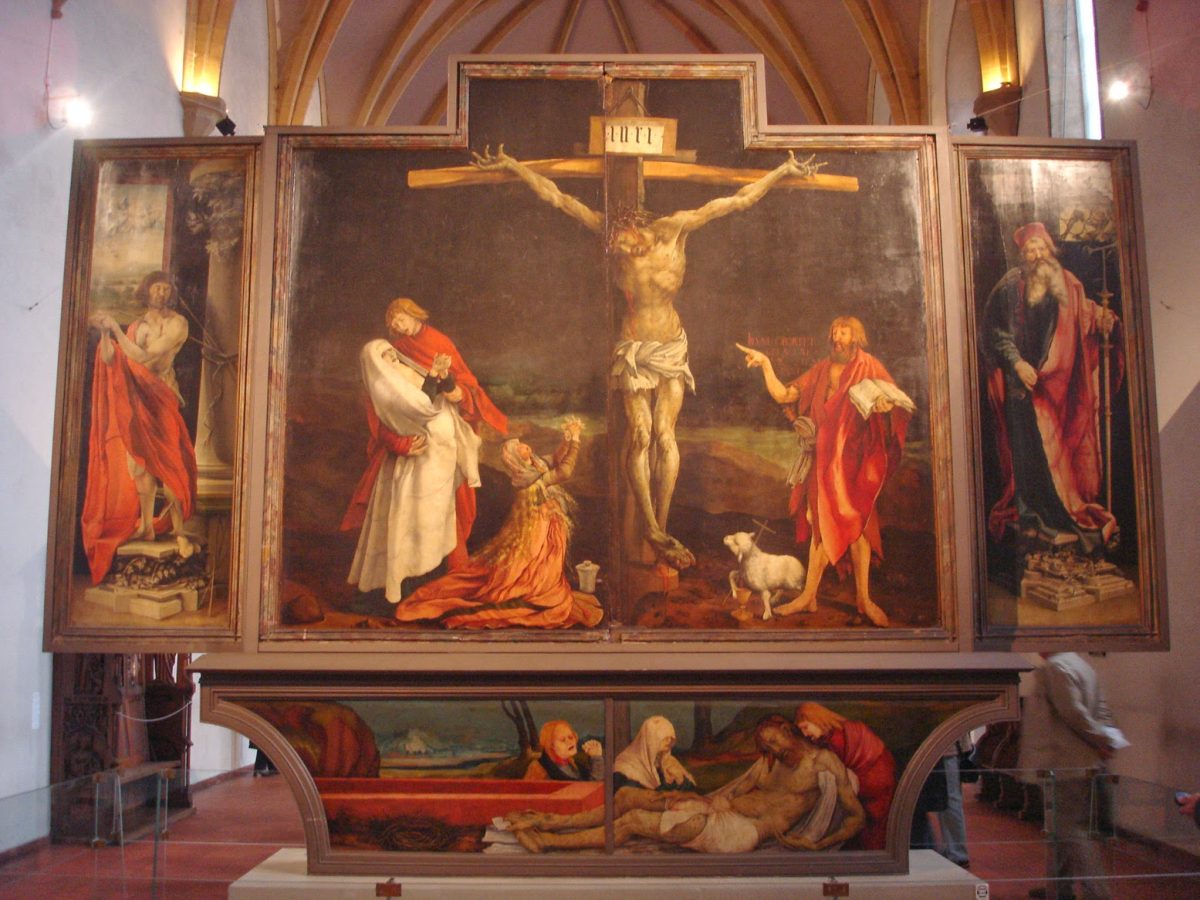

The Alsatian city of Colmar in France near the German border is home to the Isenheim Altar piece, regarded by many as the most moving depiction of the crucifixion ever created. It was made by Matthias Grunewald for the monastery of the Antonian Hospitallers, a community dedicated to caring for victims of the many plagues which afflicted Europe in the late middle ages. Grunewald depicts Jesus as one of them. His twisted body on the cross is covered in the pock marks and boils of a plague victim. Before this image the monks and their patients would pray drawing consolation from knowing that in their suffering, they were participating in Christ’s who “in his affliction had become one with all the afflicted of history. Looking, they were drawn into the abyss of everlasting mercy”. (Joseph Ratzinger).

Just up the road from Colmar and the Isenheim altarpiece, in the Voges mountains, is the village of Natweiler and the only Nazi concentration camp to be found on present day French territory, Natweiler-Struthof. It is a haunting place, like all such places. What I remember about the day my friends and I visited, the same day we visited Colmar and the Isenheim crucifixion, is that you stand on a height looking down a hillside to innocuous rustic buildings at the bottom. Inside are the gas chamber and the oven. Standing in the quiet and beautiful countryside, it is hard to imagine what went on there.

Many in our society, looking at the Natweiler Struthof camp and all that it stands for, say: in the light of this, how can there be a God?

But, strangely, it is often the comfortable on-lookers, the tourists of misery, who dismiss the possibility of God, and those who are actually experiencing his absence, in their own bodies, who discover him. This was the purpose of the altarpiece in the Antonian hospital in Isenheim in the 16 c. We do not have any actual testimonies from the patients who prayed before it, but the intention of the brothers was that those gazing at the altarpiece, almost as into a mirror, would see God taking their affliction upon himself, identifying with it and thereby redeeming it. The Antonian order had 369 hospitals: they were major health care providers, so they did not have their heads in the clouds, providing cheap solace to hopeless cases; they were on the ground, right among the loveless and unlovely, tending those ghastly wounds.

The Isenheim altarpiece and the Struthof death camp are around the corner from each other, and even though the historical events they represent are separated by so many centuries, each is “a thing beyond telling, out of the reach of words.” (So said the jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin of the Grunewald crucifixion, a copy of which he kept in his office.) (quoted in Rutledge Fleming “The Crucifixion”).

A thing beyond telling, out of the reach of words.

The implication would seem to be that the only possible, the only true response to such evil and suffering is silence. And, indeed, there are those who warn that to try to depict what happened, to write about it, theologize about it, make music about it only ends up trivializing it, because it is indeed a thing beyond telling.

In his great novel of the persecution of Christianity in 17th century Japan, entitled “Silence”, Shusaku Endo describes the terrible suffering of Japanese Christians who are tortured until they renounce their faith. The European missionary priest Rodrigues, listening to the groaning voices of the victims all around him in the darkness of his prison cell, denounces God for his silence:

“Lord, it is now that you should break the silence. You must not remain silent. Prove that you are justice, that you are goodness, that you are love. You must say something to show the world that you are the august one.”

This Good Friday, like every Good Friday, we have reason once again to make the same demand. Whether it is the discovery of yet another corpse of a murdered Indigenous woman, or the brutal stabbing of a boy sitting alone on a bench in a subway station, or the latest atrocities in a European war we thought could never happen again, or our own private suffering and that of those we love, we, too, this Good Friday have reason to demand that God not remain silent.

The Church throughout the world now enters a period of the most profound silence, unlike any other time in the year, the silence of Holy Saturday, the time of the burial of Christ, of the rolling of the stone across the tomb’s entrance after they had laid him there, no light penetrating its darkness. Apart from the Office, there are no liturgies in the church on Holy Saturday, nothing to look at, nothing to listen to, no prayers to say, no hymns to sing. Silence.

Paradoxically it is often a day of great activity among us, especially in sacristies and vestries as the polishing and decorating reach fever pitch in anticipation of Easter. But that only heightens the theological paradox, the emotional complexity of this in-between time.

The Apostles’ Creed makes the period between the death of Christ and the first announcement of the Resurrection a statement of Faith for Christians: “He descended to the dead” we recite, or in the old translation “He descended into Hell.”

What can this mean? Some have said that the silence of Holy Saturday is the silence of God’s utter abandonment of his Son, that even more than the crucifixion itself, the descent of Jesus to the dead represents the deepest point of his solidarity with us. This is the silence of the God who voluntarily empties himself, becoming as silent in death as we do, “lost among the dead”, in the words of the psalmist. (Ps 88:5)

But there is another and more prevalent understand of the Silence of Holy Saturday in the tradition, based perhaps on the 1st letter of Peter who speaks of Jesus after his death, making a proclamation to “the spirits in prison”. The Silence of this Holy Saturday is real but is masking great activity, nothing less than an invasion of Hell by Christ who comes to conquer death, grasping Adam and Eve by the hand, the deluded parents of humanity, and dragging them up out of the darkness. Images of this Harrowing of Hell depict great processions of those languishing until now in the dark for untold eons, moving to the light, the demons, in anguish, scattering before them.

Both versions of the Silence of Holy Saturday are needed perhaps for us to understand the depths of the mystery of our redemption, taking place silently, out of sight, but no less truly.

Surely the descent of Christ to the dead, to Hell, means that there is no part of God’s creation, seen or unseen, that his mercy cannot reach. That even the Judases, the concentration camp guards, the torturers, not to mention the everyday failures like you and me, can escape from the mercy of Christ pursuing into the darkest places of our lives, confronting us, and offering his hand to pull us up. In his poem the Hound of Heaven, Francis Thomson, who knew more than most the darkness of addiction and despair refers to Christ as “this tremendous lover who pursues us with “unperturbed pace, deliberate speed, majestic instancy.”

In a few moments we will join a procession to the cross, the figure of our dear Lord fixed upon it. There we will behold his fair beauty not because we trivialize or fetishize suffering but because we know that beyond the worst degradation that can be brought upon humanity, which God has taken upon himself for our sakes, there is the light of Easter. Eastern Christians speak of the “bright sadness” of Lent and Holy Week.

It would certainly be unseemly to sing our alleluias out loud just yet, but as we approach the Crucified One today in wonder awe and love, it would not be inappropriate to whisper them quietly in our hearts as we do so.