By Rev. David Brinton

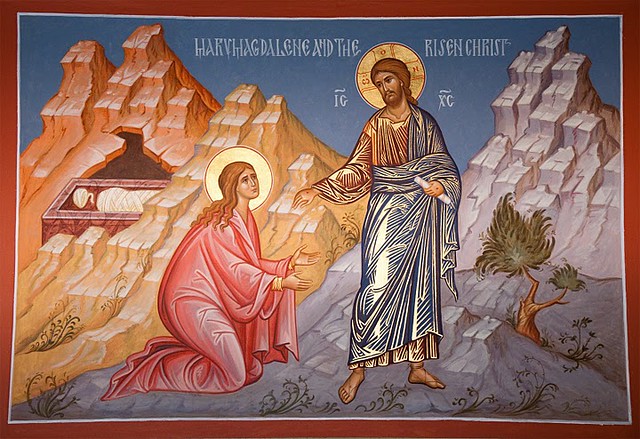

The terrified myrrh-bearing women, looking for the body of the Lord are greeted by the angels at the empty tomb with these words: “Why do you seek the living among the dead? He is not here. He is risen.” They are words for every seeker to take to heart, every Christian, and in a particular way, I think, every Christian monk or nun.

The gospel suggests that if you want to know Christ and see Christ and follow Christ you must not look for him among the dead, the static, the stuck, like an artifact to be analysed. “You must rather allow yourself to be moved and guided by him for he is the living movement of life….we encounter him only when we follow him and only by following him do we see him.” (Joseph Ratzinger).

That point is made in the gospels of Matthew and Mark where the women are explicitly instructed to tell Peter and the others to follow the risen Jesus into Galilee, only then would they see him. Luke doesn’t include that detail about going to Galilee to discover the resurrected Lord, but instead gives us the beautiful travelling story of the encounter on the Road to Emmaus on the evening of Easter Day which suggests in its own way that it is in moving with Christ that we gradually begin to see Christ.

To follow Christ where he goes, to walk behind him and with him, is to enter into the wounded world he died for, into “Galilee”, in witness and loving service. But this following is only possible because we have followed him in his death, resurrection and ascension back into the heart of the triune God from whence he came. We do not make either of these journeys alone, but in the communion of his body the Church, itself always on the move towards him, renewed and strengthened for the journey by the Holy Eucharist.

The Resurrection as movement, finding Jesus not among the dead but the living, was so eloquently shown in the procession with which we began, the darkness of death and the grave all around us pierced by the light of the Paschal candle representing the risen Christ, the night glittering with the tapers of his followers as we moved, sometimes in a straight line, sometimes in a circle but in the end always moving forward, towards the destination he has fixed, following him into the promised land of fellowship in the life of the blessed Trinity, and loving service in the world.

In English we call this day and season Easter. But most of the world calls it some variant of the word “Passover” (pascha, paques, pasqua, pascua), a word that comes to us from the foundational story of the Jewish people, God’s liberation of the ancient Hebrews from slavery in Egypt, and their passage through the Red Sea to freedom in the promised land.

The proper noun Easter probably comes from the name of a goddess worshiped by pagan Anglo Saxons in the north of England until the coming of Christianity. She was a goddess of the dawn, of the rising sun, of the East, and so it was natural that the word came to be associated with the rising from the dead of the Son of God.

But Easter can also be a verb. In nautical terms, a sailor “easters” when he turns the ship towards the east, to the source of light. In this verbal form, the word is a good description of the Christian life as movement, as turning, a life characterized by conversion, continual re-orientation, literally “turning to the “orient”, to Christ, who every morning in the church’s daily prayer is called the “dawn (or dayspring) from on high” who brings light to those who sit in darkness and the shadow of death.

The most famous use of the word Easter as a verb is found in Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “The Wreck of the Deutschland” in which he says of Christ: “Let him easter in us, be a dayspring to the dimness of us, be a crimson-cresseted east”,

This sense of Easter as movement, turning towards the risen Christ and following him is evocative of one of the key elements of Benedictine monasticism which has influenced all monastics including the Sisters of the St John the Divine. Along with stability, (commitment to a place) and obedience, (to an Abbot or Abbess) there is the promise to be faithful to “the monastic way of life”, in Latin, conversatio morum. There is lots of speculation about what Benedict intended by the phrase, but the original Latin implies this commitment to a lifestyle as embodied in a particular community involves both conversion and conversation, growth, engagement, movement. For monastics, today’s gospel injunction not to seek Christ among the dead, but the living, to be continually “eastered”, to change direction and be steered towards the Son, suggests that being faithful to the monastic way of life is far more than submitting to a set of rules and customs while privately pursuing one’s individual journey to God. The community, warts and all, is to be the context for a brother or sister’s continual conversion, his or her movement towards Christ. One monk’s salvation in some sense is inextricably linked to every other monk’s. This witness to the common life as a vehicle of sanctifying grace is prophetic and of enormous value in the life of the church.

What is it like to be “eastered”, to not only celebrate Easter, but to let Easter work in us?

To let Christ easter in us, to be a dayspring to the dimness of us, is to discover more and more that we do not possess the truth, either about ourselves or about others, or about God, as something static we can cling to, but rather that the Truth possesses us. This “truth from above” is dynamic, always drawing, nudging us forward into the great procession of the Church to the dawn.

St Augustine, in an ecstatic mood, preached about this movement of the Church towards Christ: “How happy will be our shout of Alleluia there – how carefree – how secure from any adversary, where there is no enemy, where no friend perishes…So, …let us sing ..now, not in the enjoyment of heavenly rest, but to sweeten our toil. Sing as travellers sing along the road, but keep on walking. Sing, but keep on walking. What do I mean by walking? I mean press on from good to better. The apostle says there are some who go from bad to worse. But if you press on, you keep on walking…So sing..and keep on walking.” (quoted in Kenneth Leech).