By Sr. Constance Joanna, SSJD

Genesis 45.3-11,15 / Psalm 37.1-12 / 1 Corinthians 15.36-38,42-50 / Luke 6.27-38

I find the readings this morning unusually challenging. They make us come to grips with some paradoxes and apparent contradictions in our theology around a God of unconditional love and how things just don’t turn out the way a lot of our scripture makes it sound like they will.

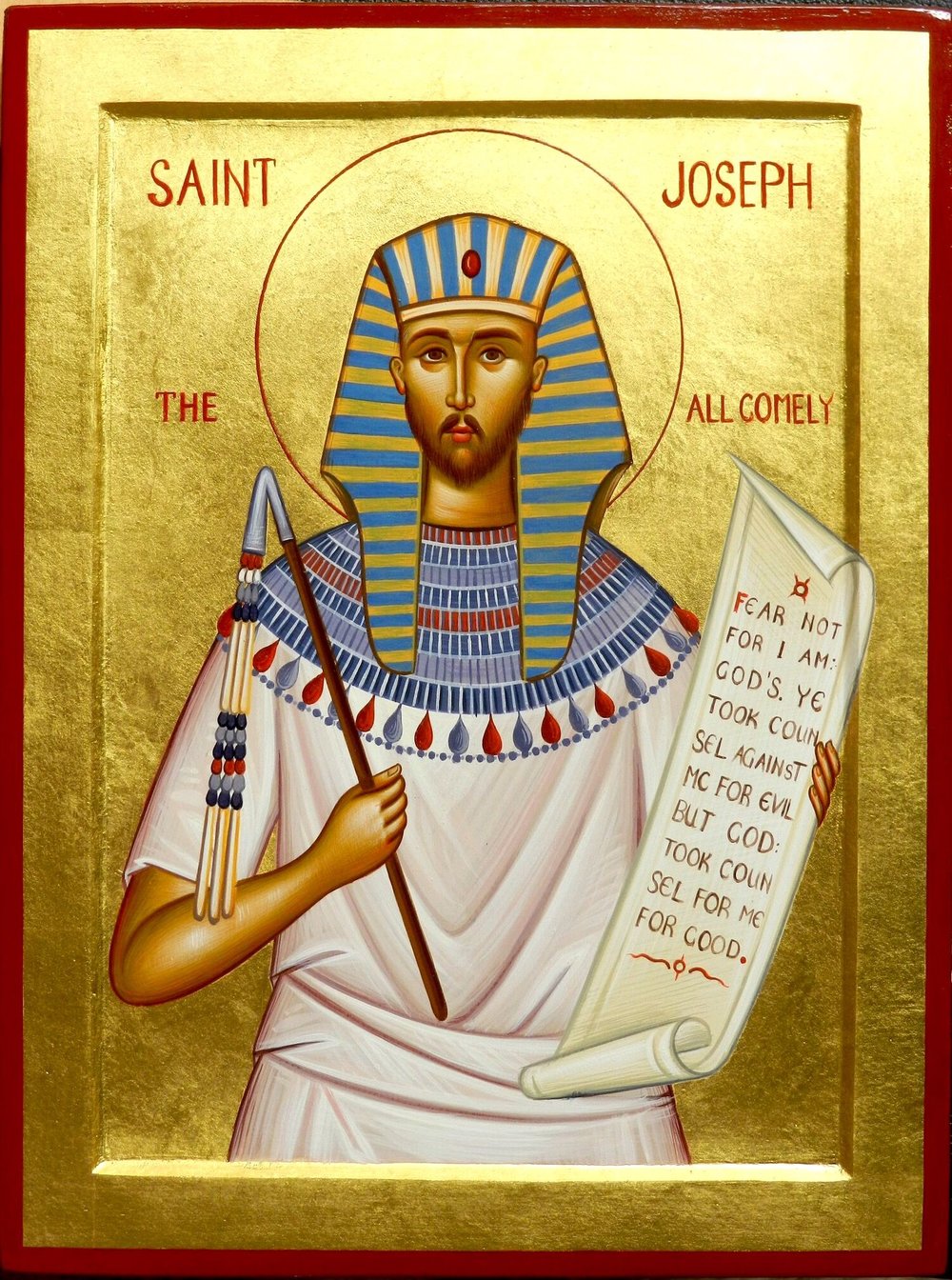

The most evident conundrum for me is in the reading about Joseph. On the one hand it’s a beautiful story of forgiveness and reconciliation. On the other, it raises some questions about what it means for God to be the God of the Hebrew tribes.

When Joseph’s brothers weep in repentence at having sold him into slavery, Joseph said, “Do not be distressed or angry with yourselves because you sold me here; for God sent me before you to preserve life.” Did God engineer Joseph’s brothers actions in order to find a way out of a future famine for Joseph’s family? It seems extreme. Clearly Joseph’s position next to Pharoah in Egypt turned out to be a good thing, and it ended up with the Israelites going into Egypt for economic reasons. They were in the midst of the famine, and Joseph had created a plan for Egypt that ensured they would be able to buy food. But does this mean that God saved the Israelites by making slaves of them?

There is another question that underlies that one for me: throughout the Hebrew scriptures there is a promise that God will kill our enemies – the ones who break the covenant – and save those who are faithful. We even see it in the song of Hannah and the song of Mary: God casts down the mighty and raises up the lowly. But that rarely seems to happen (you only need to think of current dictators who run roughshod over the lives of ordinary innocent people).

Furthermore, just because we are good and holy (whatever exactly that means) does not mean that we will be successful or rich or powerful. Some people explain this in an other-worldly way. The bad people will be sent to hell or at least to a long purgatory, while the good people will go straight to the pearly gates and be welcomed with open arms by Peter if not by Jesus himself. But we don’t really believe that do we?

On the other hand, neither do we believe that bad people will be killed and the good saved. Otherwise how do you explain the presence of martyrs in the church? The martyrs all seem to be good people who get killed because they’re on God’s side. In fact that’s part of the definition of a martyr. You have to be good and faithful. No one called Hitler a martyr when he was killed.

I am puzzled by these questions every time we recite Psalm 91 at Compline – God does not keep plagues away from our dwellings no matter how good we are. And in today’s Psalm 37 we see a similar conundrum:

“Do not fret yourself because of evil doers; do not be jealous of those who do wrong.

For they shall soon wither like the grass, and like the green grass fade away.”

I don’t want to leave you or myself feeling depressed about these difficulties in Biblical interpretation, so I want to suggest two things that help me. They don’t answer or explain everything – maybe not much at all. Theologians have been trying to do that for centuries. But they give me some faith in a just and loving God.

First, it’s important to remember that the history of God’s people in scripture is dynamic, always changing as the centuries pass. The earliest events of the Old Testament are stories meant to explain the origin of the world and the presence of evil in a world created by a good God; they are communal myths that give meaning to the actual historical events of the Hebrew scriptures, but even those are not factual history in the way we would think of it today. There is more than one version of many events, and they were passed down in oral tradition and not written down until centuries later. What we have in these stories is part history, part a continuing attempt to explain the ways of God with mortals. As we move through the Old Testament, in the prophets and other non-historical writings, we see the understanding of God subtly shifting and changing from a tribal God-hero to an understanding of the creator of the universe. So that person who wrote down the Joseph story is not reflecting the historical Joseph’s understanding of events so much as trying to explain things in the writer’s context many years later. The sad thing is that these tribal ideas still persist. You even see it at football games when the players huddle to pray. (But then the other team is huddling to pray too – it puts God in a difficult position. Does God play favourites?) Even more, you see it all the time in war, all over the world at this time.

The second thing that gives me comfort and faith in a just and loving God, is supremely Jesus. His very presence is not always comforting because it doesn’t look like God treated Jesus very well (or as Teresa of Avila said, if this is how God treats his friends, how does he treat his enemies). However what gives me comfort is that Jesus was not just a son tortured and mistreated by his father God. Jesus was God incarnate, and was the target and victim of the evil in this world. Jesus resists Satan’s attempt to get him to jump off the pinnacle of the temple (and interestingly it’s Satan who quotes Psalm 91– he gives his angels charge over you.) Likewise Jesus resists the temptation of the crowds at his crucifixion to save himself. Our God is not our personal magician who makes things work out for us, but a God who suffers with us.

The letter to the Corinthians clarifies this shift from the theological assumptions in Genesis to the understanding of God in the gospels and the subsequent epistles, where God is a God of unconditional love who suffers for us and with us. Paul says it this way in Corinthians:

“What I am saying, brothers and sisters, is this: flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable.”

That’s the most important lesson of today’s readings I think. We cannot confuse the heavenly and earthly. There is a dimension of human life that goes beyond the polarities of good and evil as we categorize them on earth. There is something about the love of God as seen in the incarnation, which is deeper than any theological explanations of God that we can think of. It is the principle behind this morning’s gospel. It’s what enables us to love our enemies, to do good to those who hate us, to do good expecting nothing in return, to refrain from judging because only God knows what is in the heart. We don’t do good in order to please God or win God’s favour. We do good because it is the outflowing of God’s love in in us.

In our community gathering yesterday morning we sisters talked about what it means to be “in Christ,” and I believe that both Luke and Paul, in our readings this morning, are saying that loving others unconditionally is what happens when we live in Christ. And being able to receive love is also what happens when we live in Christ:

“A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap.”

And that good measure will allow us to grasp at a visceral, feeling level, what it means to worship a God of both justice and unconditional love. We don’t have to solve the theological conundrums. We just need to live in Christ as individuals and as a community.