By the Rev. Frances Drolet-Smith, Oblate SSJD

The hope and joy we always anticipate of the Resurrection has been revealed to us. Depending on where you live, spring may have already made a welcome entrance with its usual gorgeous palette, accompanied by a fanfare of glorious bird song, floating on warmer breezes.

Now, these poetic predictions are based on what has happened at the end of every other Lent I have ever known but I must admit that the cataclysmic impact of Covid-19 and its subsequent rapid spread around the world, has curbed my enthusiasm. The World Health Organization declared this a pandemic in the middle of the second week of Lent and so schools were soon closed, non-essential businesses shuttered, church services cancelled, and the world sent indoors. Not only were our traditional Lenten observances curtailed by the necessary restriction on gatherings, our attention shifted to more solitary practices. For me, the words of the psalms, particularly the psalms of lament, became a vehicle for prayer.

Lament is a poetic form that gives voice to our grief and sorrow. It is a prayer that enables the unburdening of our soul. Questions like “what’s next?”, or “how long”, or “where are you?” often dominate a prayer of lament for in lament, we have permission, or perhaps we take license, to pour out all our anxieties, even our rage. And though we may think it’s the “wrong kind of prayer”, we are in good company.

The writings of the prophets and the Psalms are filled with laments; there’s even a whole manuscript in the Hebrew scriptures called “The Book of Lamentations”. They are more than mere complaints – they are words of raw, unguarded emotion. Jesus prayed prayers of lament. After supper with his friends, he went out to the garden to pray and there he cried out “if at all possible, take this cup away from me,” revealing the daunting weight of his vocation. On the Cross, when all had deserted him except for John and the three Marys, he uttered the painfully honest question from Psalm 22 “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

If there is any gift at all in this season of pandemic it has been in recalling the value of lament. Lament asks the two pivotal questions which shape our relationship with God: “Where are You?” as in, “Where can I find you present?” and “Why?”, as in, “Where is your Love in all this?”

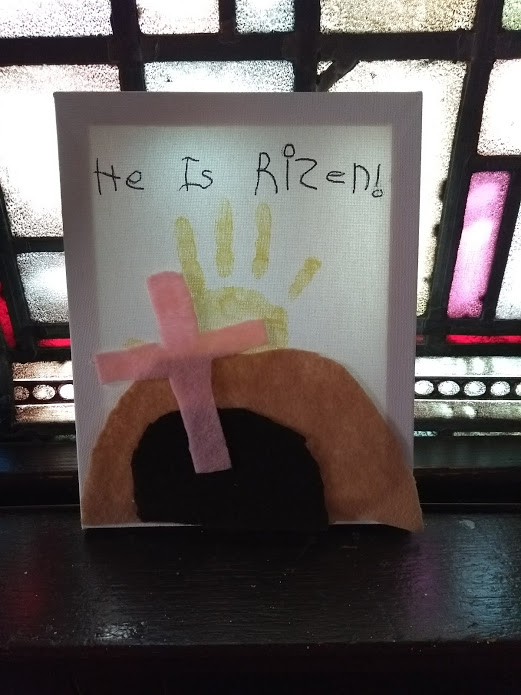

While the joy of Easter is something that has always been assured, this year will surely feel different from any other. What I hold on to, what the Cross reminds me is that life is not all bunnies and pretty ribbons; it is also the minutia of life, all the unknowns, all the uncertainties. And God, present on the Cross in Jesus, is also very present at the crossroads of life: in all the ERs, beside all the beds, in all the alleys, and in all the sobs of anguish and fear; in all the words complaint and resignation. These weeks leading up to Easter have truly been a desert, where many have felt deserted and afraid. It was in this crucible I put together some words that are psalm, lament, and prayer combined, hoping to express the flicker of hope I believe is still there.

Lay it all down:

Whatever you are holding,

lay it down:

the clenched fists,

the fuming tears

the consuming anger

the helpless,

exhausted sweat

and the weeping.

Lay it all down,

except for

the trowel,

the seed,

the water,

the vision of something

other than what we’re seeing now.

Whatever you are holding,

all recriminations,

accusations, protestations,

lamentations;

except for

the baby;

for those baby eyes

may well see the day

when all that people hold

are each other’s hands

and hearts

and doors

and baskets of bread

and invitations

to the banquet table,

where bread is broken

and wine is poured

and stories told

and lives celebrated

and sacred signs remembered –

and shared

where what was riven is repaired

and there is enough for all – over and to spare.

The Rev. Frances Drolet-Smith, Oblate SSJD